SAVANNAH, Ga. -- Its origin is mysterious. Its prevalence ubiquitous.

SAVANNAH, Ga. -- Its origin is mysterious. Its prevalence ubiquitous.

The growing and invasive waterweed known as hydrilla beckons hungry waterfowl, known as coots, who fall prey to a lethal blue-green algae present on its leaves. The American bald eagles that prey on the coots, themselves become prey to the algae.

Monecious hydrilla, the reservoir’s dominant aquatic plant, provides a substrate for algae carrying a toxin and also happens to be an irresistible food source for coots. The toxin is linked to a lethal neurological disease called avian vacuolar myelinopathy (AVM).

Coots contracting AVM develop microscopic brain lesions crippling their movements rendering them easy prey for bald eagles, said Jeff Brooks, a Corps of Engineers wildlife biologist.

Officials first discovered hydrilla at the reservoir in 1995. In 1998, AVM claimed its first bald eagle. Since that time, 80 bald eagle deaths (29 confirmed from AVM) have occurred in the Thurmond area with four mortalities recorded this past winter, said Brooks.

“AVM cases peak November through February when blue-green algae becomes toxic,” said Brooks. “But it’s unclear what triggers the toxin as the seasons change.”

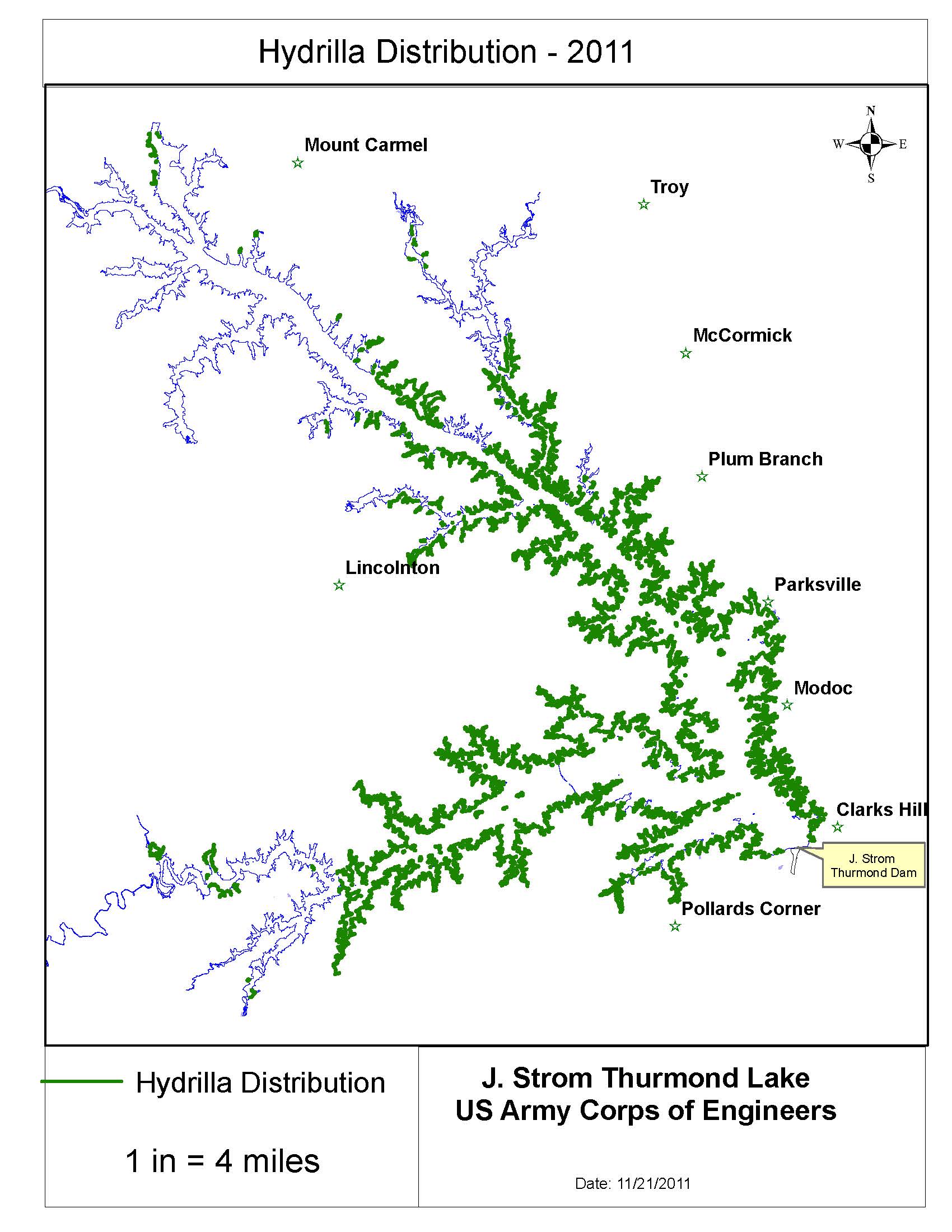

In October 2010, a survey conducted by the Corps, with assistance from the Georgia and South Carolina Departments of Natural Resources, reported that hydrilla occurs at varying densities on approximately 11,200 acres of Thurmond’s 71,000 acres. A separate survey to determine densities indicated that the average hydrilla density is 44 percent resulting in a total biomass estimate of 4,959 acres.

Hydrilla typically flourishes in shallow waters (20 feet or less) and can provide good habitat for some fish and waterfowl species. Over the years, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has used herbicides to minimize the impacts of hydrilla according to its Aquatic Plant Management Plan.

Herbicide treatments temporarily control its growth in high-use areas such as boat ramps or swim beaches, but AVM-related eagle mortalities have prompted efforts to consider widespread and long-term treatment alternatives, said Brooks.

The Corps partners with federal and state agencies to evaluate biological, mechanical and chemical treatments that are cost-effective and ecologically-sound, said Brooks.

Following the results of a 2013 survey, distributed to approximately 3,000 stakeholders designed to gauge sentiment on hydrilla issues and potential treatments, Corps officials sent a letter to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Georgia and South Carolina DNRs requesting their concurrence with an integrated plan using sterile grass carp and herbicide to control hydrilla.

Survey results found that 74.3 percent of respondents were indifferent or in support of stocking sterile grass carp – the most controversial treatment method. Even more respondents, 84.5 percent, say they prefer less hydrilla or only native plants.

“With herbicide and algaecide we know where to apply it and what the impacts are,” said Brooks. “If carp are stocked, aquatic vegetation including native plants would be consumed. We’re also in the process of completing an updated hydrilla survey to get a better handle on total hydrilla coverage.”

But Brooks warns that any alternative can potentially carry adverse impacts.

“Although stocked grass carp would require testing to determine that they are [infertile], there’s an outside chance that fertile carp could be released,” he said. “On the other hand, some herbicides can create problems for macroinvertebrates such as aquatic insects or crayfish and annual applications would be more costly than carp.”

An Environmental Assessment (EA) is underway to evaluate treatment alternatives and potential impacts to the resource. The USFWS and Georgia and South Carolina DNRs have offered technical assistance, while Georgia DNR wanted the additional details regarding treatments and potential impacts further evaluated through the EA process, said Brooks.

Corps Avian Specialist Ellie Covington helms the EA/AVM management plan and said a draft is scheduled for the end of June. The final assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact is due spring 2016.

In April 2015, UGA researchers attached transmitters to three bald eagle nestlings to determine if birds remain onsite and develop AVM or fly offsite to another location. They also sought funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for an experimental stocking of grass carp that would allow a telemetry study on carp movement in several coves at the lake.

“We’d like a consensus with state agencies on treatment alternatives because they’re involved with managing these resources as well,” said Brooks.

According to a report by Georgia Outdoor News, Georgia DNR representatives documented166 successful bald eagle nests in 2015, a record for the state.

Since their removal from the endangered species list in 2007, eagle populations continue to thrive nationally. Although AVM threatens bald eagles on or near Thurmond waters, it’s largely a local issue isolated to Thurmond and has affected several other lakes throughout the southeastern U.S., including DeGray Lake in Arkansas, which recorded the first confirmed AVM eagle death in 1994.